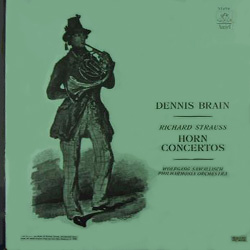

Dennis Brain could have left no more eloquent testimony to his artistry and no more treasured legacy for the world to enjoy than his new Columbia record (33CX 1491) of the two Richard Strauss Horn Concertos with Philharmonia Orchestra conducted by Wolfgang Sawallisch.

Both concertos are in themselves amiable, lyrical music, flashed with brilliance in their demands on the solo instrument and in their layout for orchestra, and the performances preserve for our delight the masterly virtuosity and integral musicianship that was Dennis Brain's unique hallmark. His death in a car accident on September 1 was universally mourned, yet we may be grateful for the example his remarkable career has bequeathed to us.

He was the third generation of expert horn-players in one family, the son of Aubrey Brain and the grandson of A. E. Brain, one of the founder-members of the London Symphony Orchestra in 1904. Grandfather Brain, with his LSO colleagues Adolf Borsdorf, Thomas Busby and Henri van der Meerschen, made up an orchestral horn quartet of such brilliance that they became irreverently known as "God's Own". Aubrey led an equally distinguished career in major orchestras until his premature retirement in 1945, by which time Dennis was well established as the foremost exponent of his instrument-and anybody who has ever tried to produce coherent sounds on a French horn will tell you what that implies.

Someone once wrote to George Bernard Shaw, in his days as a music critic 70 years or so ago, enquiring whether there was such a thing as a "dumb horn" like the dummy piano keyboard sometimes used for teaching fingering. Shaw characteristically replied in one of his articles:

Bernard Shaw's Irony

"I am happy to assure him that no such contrivance is needed, as the ordinary French horn remains dumb in the hands of a beginner for a considerable period. Nor can anyone, when it does begin to speak, precisely foresee what it will say. Even an experienced player can only surmise what will happen when he starts. I have seen an eminent conductor beat his way helplessly through the first page of the Freishütz Overture without eliciting anything from the four expert cornists (sic) in his orchestra but inebriated gugglings".

That of course was before the Brain family started taming the orchestra's most treacherous instrument. I sometimes wonder whether Shaw ever heard any of the results, for not the least remarkable thing about Dennis was the impudent assurance with which he could make his instruments speak exactly what he wanted it to say.

Not only did he throw off the most difficult feats of virtuosity without turning a hair but, what was even more important, his presence in an orchestra like the Philharmonia (where he was principal horn from its inception) gave a rock-like confidence to players and conductor alike in sustaining them through many an awkward passage.

Such moments as the opening of the Freischütz Overture already mentioned, the Trio of the Eroica Symphony, the beginning of the slow movement in Tchaikovsky's Fifth Symphony, a host of passages in Strauss like the opening of Till Eulenspiegel and that hauntingly beautiful ending to September in the Four Last Songs demand the most exemplary technique combined with eloquence of phrasing. Dennis could be relied on to give as faultless a performance in these as in long concerto or chamber group solos, and his recording of them on many discs with the Philharmonia Orchestra will be as impressive a memorial as his solo performances.

Relatively few examples of his solo artistry exist on record, the fault primarily of the repertoire, which was in turn due to the notorious unreliability of the instrument. Haydn and Mozart both wrote Horn Concertos (Dennis has recorded the four Mozart concertos on one LP), but they were for the old hand-horn without valves.

Halévy's opera La Juive (1835) was the first orchestral score specifically to feature a valve-horn, and Schumann the first composer to write for it as a solo instrument with his Adagio and Allegro for horn and piano in 1849. He also wrote a charming little Concertstück for four horns and orchestra, with the first horn part so tricky that it is seldom attempted. Whether Dennis ever performed it I do not know, but I shall always regret never having heard him in it.

His Current Records

Apart from the Mozart and Strauss concertos, the only works now in the record catalogues that feauture Dennis as soloist are the Mozart Quintet, K.452, Beethoven's Quintet, Op.61, Lennox Berkley's Horn Trio and Britten's Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings, composed especially for Brain and Peter Pears. Dennis was directly responsible for stimulating a number of other works by contemporary composers, including Malcolm Arnold, Gordon Jacob and Hindemith, but of these only Hindemith's Horn Concerto (1950) was recorded in time and apparently the only Dennis Brain solo recording still left to come.

Tapes of other performances, like the Dukas Villanelle mentioned by a correspondent last month, may exist through having been taken by the BBC from broadcasts, but to what extent these may be available or even fit for issuing on ordinary records I cannot say. While we naturally want to be able to hear as much of him as possible, I feel that to issue anything technically inferior simply for the magic of a name-as has happened with Toscanini, for instance- would be a grave mistake.

What we have is so little in quantity, yet it is so much in terms of quality. It used to be said of Aubrey Brain that even if he blew into a length of gas-pipe it would still sound like Aubrey Brain. The son went one better and carried a length or two of rubber hosepipe around with him for demonstration purposes at lecture-recitals, even bringing them to the Hoffnung Festival Concert in the Royal Festival Hall a year ago where he performed an entire Leopold Mozart Concerto on hosepipes tuned to appropriate keys.

But these were the freaks of virtuosity; the genuine skill went to the polishing of an immaculate technique at the service of the composer, and Dennis had been doing that ever since he first started playing with the Adolf Busch Chamber Orchestra in 1938. In the same year he made his first record at the age of 16-a Mozart Divertimento with a group that included his father and the Lener Quartet. The war years were spent in the RAF Central Band, and afterwards, in addition to his work with the Philharmonia and Royal Philharmonic Orchestras and his solo appearances, Dennis formed and toured with his own Wind Ensemble.

"He lived modestly, and he worked like a ...," said a friend of his to me, and there could be no simpler or more truthful epitaph. The happy serenity of his nature is reflected in the warm, unmistakable tone of his playing, and the calm skill he brought to his inherent musical flair. What we expect of art is not ease but difficulty, for it is in creating the illusion of ease that we find all the pleasure of virtuosity and understanding.

The Two Concertos

FATHER STRAUSS: Franz Strauss, father of composer Richard, and for whom the first Strauss Horn Concerto was written, is pictured on the sleeve of the new Columbia disc.

Franz was one of the finest horn-players of his day.

FATHER STRAUSS: Franz Strauss, father of composer Richard, and for whom the first Strauss Horn Concerto was written, is pictured on the sleeve of the new Columbia disc.

Franz was one of the finest horn-players of his day.

Strauss appreciated this well enough when he composed his two Horn Concertos-the first in 1883 for his father, Franz Strauss, who was then principal horn in the Munich Opera House orchestra, and the second in 1942. Some 60 years thus separate the two works, and the style of them is comparably different.

The first, composed when Strauss was 18 years old, is hardly more than a youthful filial tribute, reminiscent of Schumann and Mendelssohn in its conventional musical idiom but with attractive melodies that ideally suit the solo instrument. Even though the use of valves gave the player command over the full chromatic scale, "open" notes still produce the best fullness of tone and Strauss used themes where the notes requiring valves are of lesser importance.

He did much the same thing in his Second Concerto (both are in the key of E Flat), but here the creative spirit is more adventurous, the craftsmanship more cunning and the solo part forbiddingly difficult. There is, of course, no mistaking the Straussian texture and lilt of melody such as only the creator of Der Rosenkavalier and Till Eulenspiegel could have conceived, but the beginning of the lyrical slow movement and the buoyant Rondo finale is mature Strauss at his most expressive-a style of mellow artistry that I refuse to accept, as some would have it, as representing a decline in the composer's creative powers.

If you sample this disc-and I hope that every admirer of consummate instrumental artistry will do so-try the last movement of the Second Concerto. The melody romps away in lively good humour, perfectly poised and elegantly sounded in some of the finest playing that even Dennis Brain has managed to produce. All the same, it is no isolated episode of excellence, for the solo playing is as good whether shaping the curve of a lyrical slow melody or swiftly darting over leaps and runs. Sawallisch is the rising young Geman conductor, now in charge of the Aachen Opera, whose first appearance as the youngest conductor ever invited to open the Bayreuth Festival last summer won high international praise, and who made his London concert début this month. With Dennis Brain's colleagues of the Philharmonia they partner the soloist with fullest sympathy throughout both works, on a disc that deserves to be long cherished in the whole range of orchestral music.